Middle East Eye — August 19, 2022 —-

Iraq’s Shia parties have never been so polarized, and some fear tensions could lead to collapse of the state. Here are the figures at the center of the political storm

Iraq has been no stranger to political crises since the US-led coalition overthrew Saddam Hussein in 2003.

However, the most recent development is seen by many analysts and observers as the closest the country’s fledgling parliamentary democracy has come to collapse.

Since 30 July, followers of Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr have occupied the parliament building, demanding the dissolution of the present assembly and new elections.

The occupation has come at the end of a long-deadlocked government formation process which itself came after parliamentary elections that had the lowest turnout in the country’s history.

Few can predict how the current crisis will resolve itself. Many fear that the deployment of armed forces by the different factions around Baghdad could auger the beginning of a civil war. So far, however, the different political leaders have stepped back from escalation, and there have been some tentative attempts at negotiations.

As Iraq’s political crisis continues to rumble on, Middle East Eye takes a look at some of the key players:

Muqtada al-Sadr

Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr has over the past two decades been one of the most powerful political forces in Iraq. Originally the leader of armed forces opposed to the US-led occupation, he has established himself as a nationalist and opponent of the establishment, despite many of his followers having held government positions.

Sadr’s father, Mohammed Sadiq, and father-in-law, Mohammed Baqir, were both highly influential clerics, and their faces regularly adorn placards and banners of Sadrists and other religious and political factions in Iraq. Both were killed by Saddam Hussein and are regarded as martyrs and advocates of the poor by many Shia.

Sadr himself has built a following among much of the socially conservative poor and working-class of Iraq, as well as with those opposed to the influence of Iran and the US. His base of support in Baghdad is in the sprawling Sadr City, named after his relatives, but he commands widespread influence throughout the country.

For many years after the overthrow of his erstwhile enemy Saddam, Sadr led his Mahdi Army in an armed rebellion against the coalition forces occupying the country. He would later reform the Mahdi Army into Saraya al-Salam (Peace Brigades) and become involved in parliamentary politics, calling for an end to corruption, the dismantling of the militias and technocratic reform of the country’s economy.

He has also condemned liberalising tendencies in Iraqi society, railing against LGBT people and the mixing of men and women.

His Sairoon party came first in October’s parliamentary elections (though most Iraqis did not vote), and since then he had attempted to push for the formation of what he called a “majority government” along with Sunni and Kurdish allies.

However, he was unable to secure enough support among other parliamentarians to secure the formation of a government, and in June, in a supposed attempt to break the deadlock, Sadr ordered his MPs to withdraw from the assembly.

The ongoing occupation of the Iraqi parliament, which started on 30 July, nominally came in response to the nomination of Muhammad Shia al-Sudani as a potential prime minister by the Shia Coordination Framework, the alliance of parties that have held sway in the parliament since Sadr’s MPs withdrew.

Sudani was a minister in the government of Sadr’s arch-rival, Nouri al-Maliki, and saw his nomination as an afront.

Sadr is currently demanding the dissolution of the parliament and the announcement of new elections. His armed Saraya al-Salam organisation has deployed around the parliament, although he has stressed that he wants to avoid a violent confrontation.

Hadi al-Ameri

The leader of the Badr Organisation armed faction and the Iran-backed Fatah coalition in parliament, Ameri has long been seen as Iran’s main man in Iraq, at least since the assassination of Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in January 2020.

Ameri has remained loyal to Iran for decades, even fighting on the side of the Islamic Republic in the Iran-Iraq war of the 80s. The Badr Organisation swept into Iraq following Saddam’s overthrow in 2003 and quickly embedded itself in much of the post-Baathist state, being accused of torture and carrying out sectarian killings of Sunnis.

In 2014, it joined the Hashd al-Shaabi paramilitary forces as part of the fight against the Islamic State group (IS). Badr was again accused of involvement in sectarian reprisals by rights organisations.

Despite his hardline credentials, Ameri has attempted to present himself as a moderate voice in the current dispute.

Fatah is one of the leading parties of the Coordination Framework. Though the Framework has said it is not opposed in principle to new elections, it has demanded a transitional government in the meantime and set a number of conditions on the future polls.

Fatah had poor results in October’s election, so many are wary of rushing into a new vote that could prove even more damaging for them.

Unlike some of his colleagues in the Coordination Framework, Ameri has pushed for dialogue between the different parties and has held numerous meetings aimed at trying to break the impasse. Ameri’s supporters have also not taken part in counter-protests organised by some other factions against the Sadrist occupation of Baghdad’s Green Zone.

Ameri was among those who attended a “national dialogue” meeting on 17 August aimed at solving the problem through negotiations, though with no Sadrist representative attending, it is unlikely that there will be a resolution any time soon.

Qais al-Khazali

Compared to his Coordination Framework ally Ameri, Khazali and the armed Asaib Ahl al-Haq organisation that he heads have adopted a much more confrontational approach towards Sadr.

Khazali was a one-time supporter of Sadr until he was expelled from the ranks of the Mahdi Army in 2004, reportedly after he failed to heed an order from Sadr to hold to a ceasefire with the US forces.

He formed Asaib Ahl al-Haq in 2006, and the organisation has claimed responsibility for more than 6,000 attacks across Iraq against the US-led occupation forces and their allies. Asaib Ahl al-Haq is loyal to Iran and its Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and was accused of involvement in suppressing and killing demonstrators during the 2019 anti-government protests in Iraq.

In January 2020, Asaib Ahl al-Haq and Khazali were designated as terrorists by the US State Department.

Khazali and his supporters have traded barbs with Sadrists in recent weeks in a number of forums.

Sadr’s spokesperson, a figure known as Saleh Muhammad al-Iraqi, has accused Khazali and Asaib Ahl al-Haq of thuggery and corruption across Iraq and said Khazali was part of an “evil trinity” along with former prime minister Nuri al-Maliki and their ally Ammar al-Hakim, head of the Hikma movement.

Many feared that there could be a violent confrontation between Coordination Framework forces and the Sadrists on 20 August, after they announced a counter-demonstration against a planned protest by Sadr. However, Sadr later called off the protest after he claimed that certain groups were intent on stoking a “civil war” in Iraq.

Nouri al-Maliki

The former prime minister struggled for a long time to recover his reputation after he was widely blamed for failing to prevent the takeover of Mosul by the Islamic State group in 2014, and he is often accused of overseeing and even stoking the sectarianism and cronyism that preceded it.

A staunch ally of both the US and Iran, Maliki ruled the country from 2006 to 2014, overseeing the withdrawal of American forces and then their swift return after the rise of IS. His reign became notorious for corruption, with billions of dollars disappearing from the country’s coffers.

In the October 2021 elections his State of Law coalition managed to secure the third-highest number of seats in the parliament, and as part of the Coordination Framework he has been looking to make a political comeback.

This has helped stoke tensions with Sadr, who despises Maliki for leading a deadly 2007 crackdown on his Mahdi Army. The problem worsened after the release of a leaked audio tape last month in which Maliki was purportedly heard to describe Sadr as “bloodthirsty” and a “coward” whose political ambitions would destroy Iraq.

Following the leak of the tape, Sadr demanded that Maliki leave politics entirely, and since then the confrontational stance between the two has only worsened, with the former premier being seen brandishing weapons in defiance at Sadr’s takeover of the parliament.

Mustafa al-Kadhimi

Kadhimi, who became prime minister in May 2020 in the wake of anti-government protests, has remained in his position since the October elections as Iraq’s parties have failed to form a government.

A former intelligence chief, Kadhimi initially promised he would tackle the power of the armed groups in Iraq and investigate the killings of more than 600 demonstrators during anti-government protests.

However, in the end he was able to achieve little, while armed groups stepped up attacks on US assets and even on Kadhimi’s own residence.

In an attempt to break the present deadlock, Kadhimi launched what he called a “national dialogue” process on 17 August. Although “several points” were reportedly agreed on by those attending, including Ameri and Maliki, the absence of a Sadrist representative means little has been achieved overall.

Nevertheless, Kadhimi has called on Sadr to join the process “to start a profound national dialogue and deliberation; to find solutions to the current political crisis,” according to a statement released by his office.

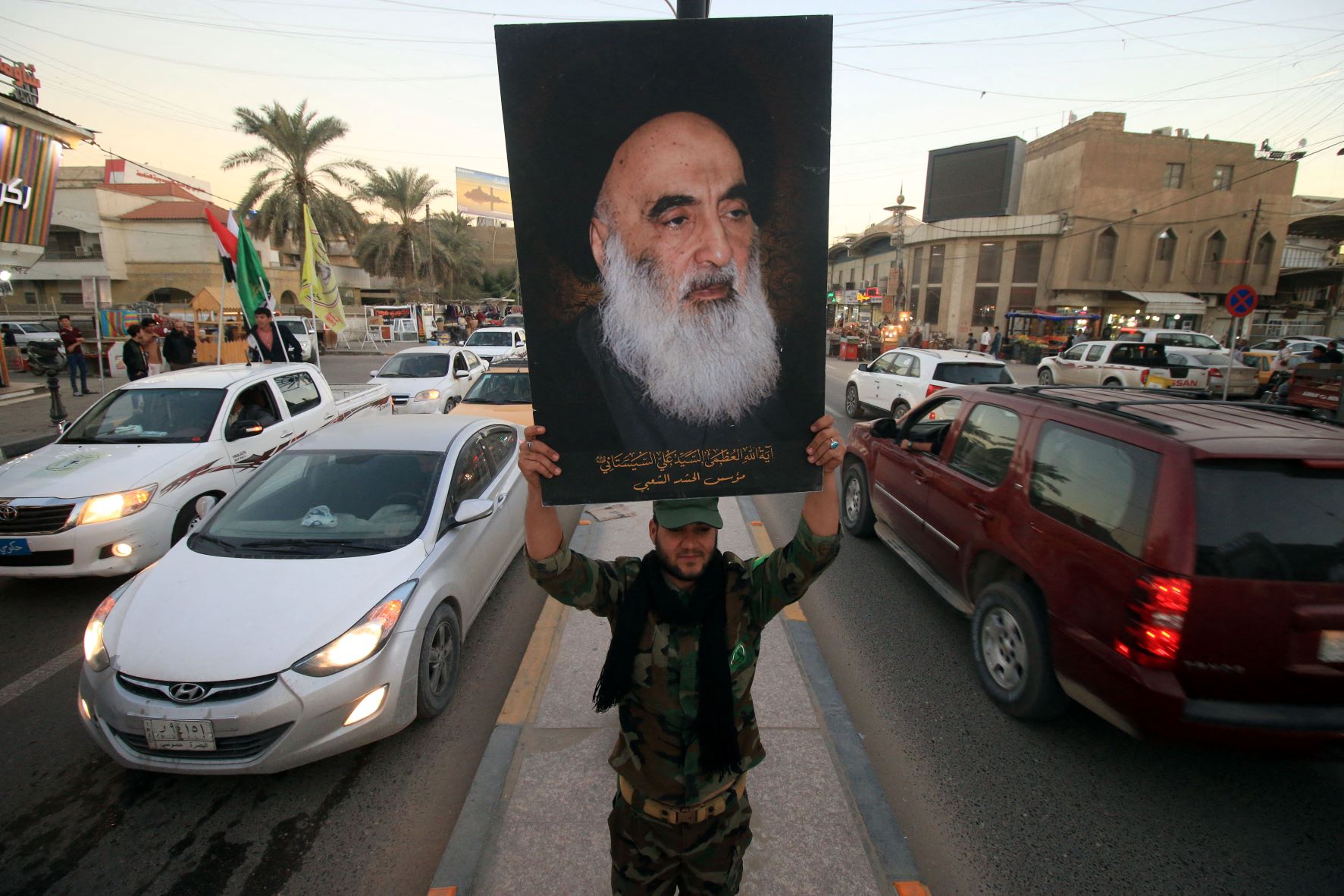

Ali al-Sistani

The most senior Shia cleric in Iraq, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, is arguably also the most influential public figure in the country.

His pronouncements on public affairs over the past few decades, including his support for the democratic process, opposition to corruption and call to arms against the Islamic State, have been seen as crucial in preventing the state’s collapse.

However, he has been quiet in recent months and has yet to intervene in the current crisis, reportedly over fears of stoking an inter-Shia conflict.

A commander of an armed group associated with Sistani told Middle East Eye the grand ayatollah will not intervene for now, but that his forces are ready if need be.

“We are worried about what is happening now, and we fear Sadr’s recklessness and the arrogance of his opponents, but we do not see the need for our intervention now,” the commander said.

Middle East Eye — August 19, 2022

URL: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/iraq-political-crisis-who-main-players