The new Magna Carta, approved in a referendum with a low turnout of 30%, stipulates that the state has to work to achieve the purposes of Islam.

www.evangelicalfocus.com – Protestante Digital · TUNIS · 11 AUGUST 2022 · 09:00 CET

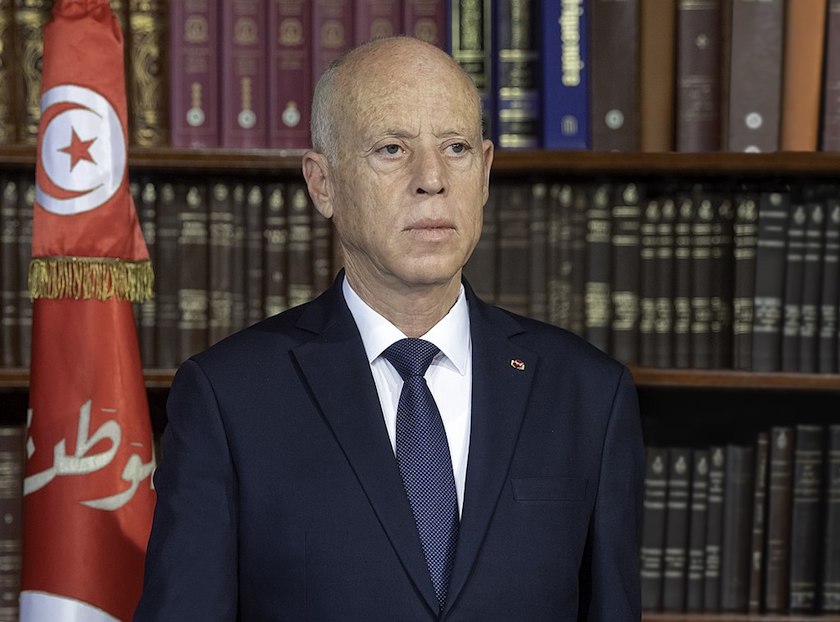

That the figure of Kais Saied is unpredictable and unsettling at the political level is evidenced by the very way he has governed since he became Tunisia’s President in October 2019. He did so by winning a presidential election, without a great display of means, appealing to promises that had to do mainly with the economy and corruption, and at a time of some instability, following the death of former president Béji Caïd Essebsi and with the vacancy being filled on an interim basis by Mohamed Ennaceur.

Since then, Saied has asserted his leadership over Tunisia with gestures that some international analysts are reminiscent again of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the dictator who ruled the country from 1987 until the Arab Spring revolution in 2011.

Until now, the most prominent of these gestures has been the declaration of a state of emergency, which has been active since July 2021, with which Saied dissolved parliament and has been ruling for one year on the basis of presidential decrees.

The latest manoeuvre has been to hold a referendum, the first in the country’s history, to vote on a new Constitution to replace that of President Moncef Marzouki in 2014. A new basic law that, according to critics, will further entrench Saied’s position by concentrating more powers under his control.

Is the referendum representative?

The statement with which Saied has proposed the referendum already highlights the very different character with which the President distinguishes his Constitution from the previous one, which was largely annulled during his last year in office. Tunisians had to answer “yes” or “no” to a question about “correcting the course of the revolution”.

The first version of the new Magna Carta was published in the Official Gazette on 30 June, and updated on 8 July with a number of changes, in a process that some, such as the Tunisian religious freedom organisation Attalaki, have criticised as “unilateral” and disregarding the opinions of experts from different spheres of society.

“The president has not taken into account the opinion of the experts who drafted the document. Nor did he take into account the dialogue that he himself promoted, nor the results of the virtual consultation that he himself launched at the beginning of the year, in which nearly half a million Tunisians participated, and whose results do not recognise the change to the Constitution”, told Attalaki’s President and co-founder, Rashed Massoud Hafnaoui, to Protestante Digital.

The new Magna Carta was approved with 94% of the votes, although for many the vote lacks legitimacy as only 30.5% went to vote. “From the stage that the country is going through from 25 July 2021 until now, with this new draft constitution or the new republic, as the president calls it, we conclude that it is important only for the President and his followers. The President is the government and the government is the President, the President is the people and the people are the President”, he remarks.

A referendum on the figure of Saied

After the referendum vote, President Saied said: “Tunisia has entered a new phase”. “What the Tunisian people have done is a lesson for the world and for history, on the scale on which the lessons of history are measured”, he says.

However, the low turnout in the referendum has tarnished his plan to pass a new Constitution with visible popular support. This broad consensus between diverse political forces and civil society as a whole was something that the European Union had stressed was necessary. Indeed, Saied’s figure has become increasingly compromised in the eyes of his own countrymen.

“Over the past few months, the streets of Tunisia have become a battleground between supporters and opponents of the referendum called by President Saied”, explains Hafnaoui. “Supporters of the referendum see it as a lifeline that will pull the country out of the difficulties and crisis left by the 2014 Constitution, and opponents see it as a setback and a step backwards that will bring setbacks to the country”, he says.

“The atmosphere in Tunisia is now turbulent” and “the division in the streets may lead to further repercussions”, Hafnaoui observes.

“The president has not changed the way he has treated his opponents, in particular, and has worked to bring Tunisians together without using the rhetoric of betrayal and division”. Hafnaoui says he favours the decision to “freeze the work of parliament”. “Since the parliament was constituted in 2019, it has spread negative messages to society and incited hatred and bloodshed”, he writes.

“However, we reject the President’s unilateral attitude and his failure to involve other national actors in building a new future for Tunisia”, the representative of Attalaki adds.

A risk to freedoms and rights

Several points in the new Constitution are causing human rights organisations to be alarmed. Human Rights Watch says the new constitution “undermines the independence of the courts, which is fundamental to safeguarding the rights of individuals”. The organisation is also concerned about how the document alters the High Judicial Council, without specifying how its members are chosen.

Attalaki also views some aspects of the new Constitution with a sense of alarm. “The new draft Constitution abolished the principle of the civil state and did not address the universal principles of human rights as principles that all nations seek to achieve within a democratic state”, says Hafnaoui. The organisation is concerned about “the lack of mention of these internationally recognised universal principles, replaced by talk of human rights in general, with the absence of the idea of a civil state”.

“This leads us to think about the future of human rights and democracy in Tunisia, which are only mentioned twice in the Constitution, where the President has replaced the concept of democracy with that of a society based on the rule of law.

In a context where human rights organisations have raised alarm over what they see as “institutional violations” in Tunisia, such as the trial of journalists and political opponents, there are serious doubts about what vision the President has about rights and freedoms. “Tunisia faces social and economic challenges in the absence of signs of stability or political progress”, Attalaki reiterates.

.

Religious freedom in the new Constitution

One of the areas where the new Magna Carta is clearer, albeit worryingly so, is with regard to religious fact and freedom. “Although Islam is no longer listed as ‘the religion of the state’, as it was in Article 1 of the 2014 constitution, Article 5 of the new constitution states that ‘Tunisia is part of the Islamic Umma’ [the whole community of Muslims] and it is incumbent upon the state alone to work to achieve the purposes of Islam by preserving soul, honour, property, religion, and freedom’”, Human Rights Watch said. “This provision could be used to justify restrictions on rights, such as gender discrimination, based on religious precepts”.

“No one doubts that the new Constitution has revived the debate over identity and religion in Tunisia, after Tunisians believed they had resolved this issue in the 2014 Constitution, following lengthy discussions among various political and civil actors. This controversy has overshadowed the other issues in Saied’s constitution. Many parties have objected to the vague references in the preamble and article 5 of the draft to the state’s relationship with religion”, says Hafnaoui.

“A Constitutionalisation of the purposes of Islam”

He also refers to the conclusions of constitutional law professor Sanaa Ben Achour, who says that “the Constitutionalisation of the purposes of Islam implies that they become the general principles of legislation in all areas”. Ben Achour adds that the President’s powers have been established in such a way that he is above all responsibility because he is considered the knowledgeable, responsible and infallible imam, trustworthy, because the inclusion of the term ‘Islamic nation’ in the country’s Constitution.

There is a risk that President Marzouki addresses the nation “as an imam, a guide”, as if he “does not need the people or the citizens to watch over him or question him, but only owe him their loyalty”, he warns.

Attalaki, which a year ago published its first report on the state of religious freedom in Tunisia and has been in contact with the administration and participated in initiatives with other entities and faith groups, considers that, based on Article 5 of the new Constitution, “nothing prevents the issuing of laws that limit public and individual freedoms in order to achieve the purposes of Islam”.

“Preserving religion, and what Muslim jurists mean by it, is to protect Islam and Muslims from the advocates of disbelief and the change of religion or the introduction of beliefs contrary to Islam and the preaching and calling for something other than Islam”, Hafnaoui points out.

In his view, the controversial Article 5 of the new Constitution is worded in a way that “does not allow for interpretation” and “opens up the conflict over identity, which can easily be used to restrict religious freedom, especially the right of religious minorities to organise and celebrate their rites freely”.

In fact, the new Magna Carta adds something that did not appear in the 2014 document, namely the possibility of practising religious services in freedom as long as “public security is not compromised”, as stipulated in article 25.

This means, says Hafnaoui, that “the Constitution can be used by the authority to restrict the citizens’ right to practise their religious rites in complete security and freedom, under the pretext of protecting religion, that is, the religion of the majority, as mentioned in article 5”.