12 AUGUST 2022

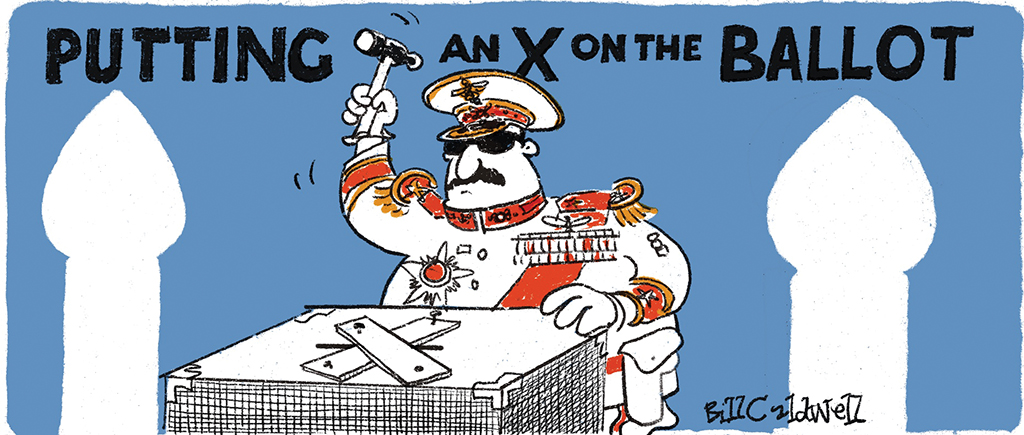

Tunisia is the latest nation to discard the democratic process. Western leaders must decide how to respond, says Gerald Butt

WESTERN leaders who are advocating wholesale changes in Arab political systems should be careful what they wish for. In 2003, the Bush administration was confident that the overthrow of President Saddam Hussein would herald the introduction of liberal democracy in Iraq. A domino effect would then flip the new system into neighbouring Arab states, and thus transform the Middle East’s political map.

The problem was that Iraq, after years of dictatorship, lacked the tools to create a workable and credible liberal democracy. Also, Iraqis were in no mood to be told what to do by invading armies. As The Economist recently pointed out, “the desert wars demonstrated that you cannot turn people into liberals by firing guns at them.”

Home-grown efforts to effect democratic change have been similarly unsuccessful. The only domino effect resulting from the 2011 Arab Spring popular uprisings, which forced several autocrats out of power, has been a relentless return to autocracy.

For example, President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt was ousted in 2011. But, eight years later, at a G7 summit in France, President Trump turned the heads of Egyptian and American officials when he greeted Mubarak’s successor, President Abdel Fattah el Sisi, by exclaiming “Where’s my favourite dictator?” All the signs are that US Presidents will have an expanding pool from which to choose their preferred autocrats in the years ahead.

TUNISIA, the sole state that appeared to have emerged successfully from the chaos of the Arab Spring, is the latest nation to discard the democratic progress of the past few years.

A late-July referendum approved changes to the constitution, transferring the reins of power from parliament into the hands of President Kais Saied. Ennahda, an Islamist party inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood, had played a significant part in creating what, for a time, appeared to be fertile ground for Tunisian democracy to grow. But opponents of Ennahda, not least President Saied himself, accused the party of corruption and incompetence in tackling worsening economic conditions.

Western governments and human-rights groups have expressed dismay at these developments. The US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, said that there had been insufficient public debate before the referendum, at which voter turnout did not exceed 30 per cent. The UK Government concurred, saying that civil-society organisations, trade unions, and the media should have been consulted. Amnesty International said that it was “deeply worrying that Tunisia has adopted a new resolution that undermines human rights . . . and fundamental freedoms”.

But that is not the view of all Tunisians themselves. The former Archbishop of Alexandria, Dr Mouneer Anis, said: “Our congregation are very happy with the new constitution because it affirms freedom of belief. It also states that Tunisia is a secular country, not an Islamic one. The implication of this is great for the Christian community in Tunisia. Many people are supportive of the President because he is fighting corruption and restricting the tyranny of the Muslim Brotherhood, who previously controlled the parliament.”

Across the Arab Middle East, from the Atlantic coast to the Gulf, the dictators’ grip is tightening; but Dr Anis says that, “while autocratic rule is hard, it’s better than extreme Islamic rule where Christians would be treated as second-class citizens.”

IN SEEKING to become autocrats, Arab leaders are, without doubt, motivated by vanity and a desire to act as they please in pursuit of their goals, without the need to convince opponents of their case. As Anwar Sadat said, two decades before becoming President of Egypt: “What may be achieved ‘democratically’ in a year can be achieved ‘dictatorially’ in a day.”

Again, this is a point that appears to enjoy a measure of public support among Arabs. A recent poll conducted by Princeton University reveals that a majority of people in Tunisia, Sudan, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Libya, and the Palestinian territories say that their economies are weak under democratic systems.

They are happy to see their leaders bend the rules to get things done — if the alternative is the kind of political infighting among corrupt and powerful cliques which is seen in states such as Iraq and Lebanon, where there is a skein of parliamentary democracy. For example, Iraqis voted in elections last October, and still await the formation of a government amid intense intra-Shia struggles for power.

Given the surge of populism which is starting to erode the roots of the West’s most entrenched democratic systems, this is an inauspicious time to be pressing the merits of liberal democracy in the region.